The research aimed to identify the opinion of interested and engaged audiences on how mainstream media outlets in Brazil covered stories about Indigenous peoples and traditional communities. We also tried to pinpoint the main sources of information for the general public and for non-engaged opinion formers.

“This is the top agenda in Brazil, the big issue. Even if someone doesn't know anything about Indigenous issues, if they know that there are more than 300 human groups in the country, and that they have been trying to survive for over 500 years, they will immediately understand that we are talking about something extraordinary”, highlighted one of the journalists interviewed.

Many respondents used unflattering adjectives to describe Brazilian mainstream media coverage on Indigenous people, such as “poor”, “irregular”, “absent”, “tragic”, “sparse”, “problematic”, “prejudiced”, “alienated”, “reactive” ”, “paternalistic”, “colonialist”. Still, most respondents believe that there have been more coverage and improvements over the past decade, and that Indigenous peoples have become more visible to the mainstream media in Bolsonaro's Brazil.

A number of respondents argued that the increased coverage was also the result of behavioural changes in Brazil and around the world, such as the growth and strengthening of global fight against racism, the emerging diversity agenda, and the profusion of internet and social media content. “In addition to texts, you have what we call extra-texts: comments, social media, internet portals. These generate new texts, so to speak, in every sense. And nobody wants to get beaten, especially the most relevant media outlets.”

Jornal Nacional and Fantástico are two TV news programmes that were mentioned as examples of greater openness to Indigenous topics. “The socio-environmental agenda found, to some extent, that even the Globo network has become more sensitive.” The Globo Network also produced Falas da Terra [Voices of the Earth], a TV show described as a landmark for Brazilian TV. Falas da Terra sheds light on the plurality and the struggle of Indigenous peoples in Brazil, having Indigenous thinkers and film makers in the production of the show.

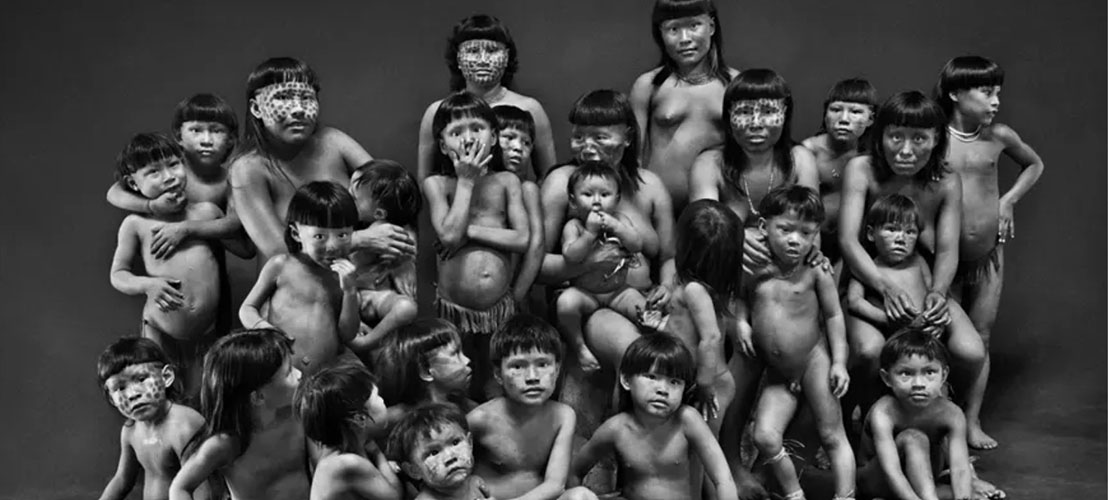

“Falas da Terra”: production team shares a bit about the program development and behind the scenes

Photo credit: TV Globo

A small number of engaged respondents were highly sceptical and negative towards the mainstream media “because of its close links with agribusiness”, “because the owners are the very ones we fight”, or “because the process of economic expansion onto Indigenous territories is legitimised by the media”.

The expansion of deforestation in the Amazon has been the main topic related to Indigenous people in recent years in the national and international press. Some respondents believe that, while it is positive that more reports on deforestation are being published, information on what lies behind deforestation, or how local populations are affected, is still often missing. In addition, the other topics that participants saw more often in the press were: the dismantling of socio-environmental public policies, environmental crimes, the increasing invasions and mining in Indigenous territories, major infrastructure works, the environmental conservation of Indigenous territories, and the impacts, losses, and deaths of Indigenous people by COVID-19.

In general, interested and engaged audiences directed most of their praise at individual journalists and shows, and not at media outlets. André Trigueiro, Rubens Valente and Eliane Brum were the most cited journalists for the excellence, relevance, and scope of their work on the coverage of topics related to the Indigenous peoples rights.

Among the non-engaged audiences, very little of what they know about Indigenous peoples and traditional communities come from fragmented pieces of information, sometimes just the titles of reports or posts on social media. The most frequently mentioned outlets by these publics were “Folha de S. Paulo”, “O Estado de S. Paulo”, “CNN”, “GloboNews”, “Jornal Nacional”, and “Jornal da Record”, as well as platforms such as “G1”, “UOL”, and “Terra”.

Among engaged audiences, only a very small number of people referred explicitly to the pro-Bolsonaro coverage of communication outlets such as Rede Bandeirantes, which went so far as to say that Indigenous people could ‘even take over Morumbi’ if the time framework thesis was not approved, according to a report by “The Intercept”.

The international press is seen as still having a huge influence in the Brazilian press coverage, and “The Guardian”, “The New York Times”, and “Reuters” were vehicles remembered for their quality, regularity, and bold approaches to reporting Indigenous people issues. The international press was also cited as a source of relevant information for economists, business leaders, and agribusiness representatives.

For several respondents, the increased coverage in the Brazilian press is considered ‘insufficient’ and ‘unsatisfactory’ given their historical omissions and distortions, and the diversity of peoples and realities throughout the country, and not just in the Amazon. Several people highlighted the need to grant more visibility to Indigenous people living in other Brazilian biomes, to those who do not spend all their time in Indigenous territories, to those who alternate their time between cities and Indigenous villages, and to those who live permanently in cities.

Reports that have no depth and no historical context, and that fail to address constitutional rights or to listen to Indigenous peoples as sources of information were cited and criticised as being responsible for reinforcing misconceptions about Indigenous peoples. The lack of qualified and consistent coverage on on the land rights of Indigenous people of Indigenous peoples was pointed out as one of the main issues.

In addition, some participants mentioned the lack of reports on the daily lives of Indigenous peoples in their territories, on the issues that permeate their lives in the present, as well as reports that value their diverse ways of life, knowledge, cultures, and cosmologies, without exoticisms. “People get married, people die, people fall in love — in short, people change, people live. There is an Indigenous day-to-day that is very heterogeneous, but that is not made visible; it is as if the life of Indigenous people only revolved around conflict.”

“We need to charm people. I think that the coverage of Indigenous issues often tends to disenchant audiences, as it is contaminated, and dominated by the oppressors. Of course, denouncing oppression is necessary, but we also have to show their enormous beauty, and their wealth of knowledge, languages, and wisdom. We must play our maracas very loud, you know?”

The generalisation, the use of inappropriate terms, or the fact that journalists still listen to scientists and not Indigenous people as specialists were other frequent criticisms of press coverage. Some journalists claimed that they felt the need to check data and information with anthropologists, for example. “There is a perception that this is a very tricky area, and there’s a fear of making a mistake, which will be read as racist, dangerous, disrespectful.”, one of the curators interviewed said.

The financial crisis affecting the national press was described as a limitation for the production of investigative reports in and around Brazil, restricting what we know about the country due to an excessive focus on the political agenda in Brasília — and even so with little contextualisation and depth.

Some people believe that the lack of depth on these topics in the press also results from lack of content and training/learning opportunities also at the journalism schools.

Although most journalists preferred not to name their main sources of information, several confirmed that they were in contact with Indigenous leaders, many of them via WhatsApp. However, some professionals, both from regional and national media, spoke about the difficulty in accessing Indigenous sources, and about the lack of feedback after several contacts and requests for interviews.

Among those professionals who do not exclusively cover this agenda, there is a feeling that certain issues tend to be avoided, such as when Indigenous people are in favour of mining or growing soy on Indigenous lands. In their opinion, these issues ought to be discussed more often and more in depth so that specific contexts could be better understood by society, including details on what (or who) led to certain decisions.

The emergence of independent vehicles such as “Repórter Brasil”, “Agência Pública”, “Infoamazonia”, and “Amazônia Real” was considered an important and positive change in the media scene in Brazil in the past decade, for “diversifying the traditional monopolies of journalistic production with high-quality investigations on topics not duly addressed by the mainstream press, such as land rights, land conflicts, and violence against Indigenous peoples”. Some shared concerns about audience reach, the difficulty of “preaching to the unconverted”, and the financial sustainability of these outlets.

Some people think that Indigenous communicators should also have more space in the mainstream press.

“It would be really nice if communication were a right, just like health and education”, concluded an Indigenous journalist.