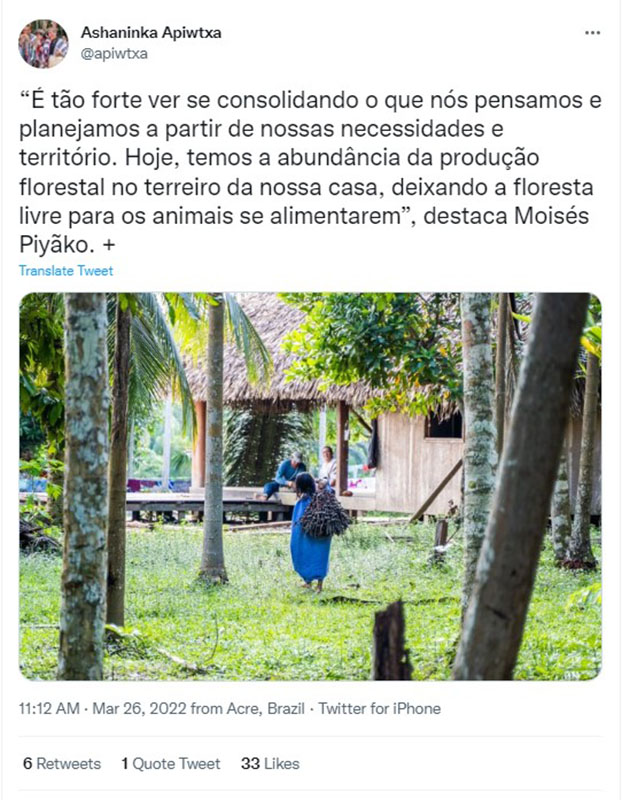

Self-representation was a keyword among the interviews. “I think the most beautiful thing about it is the production of multiple images, and the fact that they are being recorded by those who are at the forefront of the fight”, highlighted one of the curators interviewed.

Some Indigenous respondents said that visual production was critical to deconstructing stereotypes; expanding our understanding of political struggles; explaining violence and rights violations; raising awareness about the wide variety of diverse realities and peoples in the country; promoting self-affirmation and self-esteem; and recording memory. In some cases, images also help to reactivate ancient rituals or reconnect them with their heritage, inside and outside their territories.

The most frequently cited images of the past decade — both by Indigenous people and by a range of the engaged audiences — were those of Acampamento Terra Livre (Free Land Camps, or ATL in the Portuguese acronym] and of the Indigenous groups occupying iconic sites in the political capital of the country, such as the esplanade of ministries and the National Congress.

Subtitle: Mobilização Nacional Indígena Luta pela Vida

Photo credit: Apib

Interested and engaged audiences highlighted some visual interventions, such as the day when a message saying Brasil, Terra Indígena [Brazil, Indigenous Land] was written with 380 LED lamps in front of the Federal Supreme Court. They also mentioned several images of women, especially those taken during the First March of Indigenous Women, the photographs of Sônia Guajajara holding the Brazilian flag covered in Indigenous blood, and the colourful and powerful images of the Indigenous activist Célia Xakriabá.

Raoni with global leaders; Sônia Guajajara campaigning for the 2018 presidential elections, and alongside celebrities such as Alicia Keys at Rock in Rio, and Leonardo DiCaprio at the Oscar ceremony; Joênia Wapichana at the National Congress; and Indigenous artists and their works being exhibited in Brazil’s leading cultural institutions: these were some of the most iconic and representative images of the past decade. They were described as images that “expand our understanding of what it means to be Indigenous in contemporary times”, “they represent Indigenous peoples occupying spaces of power that were previously unthinkable for them”, “they show Indigenous people being valued and praised by actors that are respected by society’ and ‘they subvert commonplace and arouse curiosity”.

The international respondents highlighted the images of Indigenous participants at the United Nations Climate Conferences (known as climate summits), the Indigenous delegation touring Europe in 2019, and Raoni and Davi Kopenawa meeting political and civil society leaders.

Images of deforestation and fires in the Amazon were among those most frequently cited by most segments, in Brazil and internationally. “They are eloquent records of a world shared by all of us, but which is being destroyed. They produce an iconography of the end of the world, which is not in the future, but is happening today.”

Satellite images of the Amazon were often used by Brazil interviewees to describe the reality in Indigenous territories: “You can see it on satellite images, and it becomes evident: areas inhabited by Indigenous groups are the greenest ones”.

For foreign participants of the research, especially Europeans, images of deforestation are gaining new layers of meaning, increasingly associated with products consumed by the global North and China (such as beef), and the impacts of pushing the agricultural frontier into forests and territories belonging to Indigenous peoples and local communities. They also spoke about images of Indigenous people using technology and drones to defend their territories as images that called their attention.

Images of Brazil's environmental collapse, in particular the expansion of illegal mining on Yanomami and Munduruku Indigenous territories, and land conflicts and environmental crimes such as those in Mariana and Brumadinho, in Minas Gerais, came up very often in the responses. “The aerial images of Indigenous lands, both the deforestation and the destruction of their territory by mining, those holes in the ground, that is absolutely terrifying.”

Still on the images of resistance and confrontation, Belo Monte hydrodam was once again a reference, in particular the images of Indigenous protests against the construction of the hydroelectric power plant.

Credit: Bruno Kelly/Amazônia Real

Images of murdered Indigenous leaders were widely cited, leading to discussions about how best to portray violence against Indigenous peoples. The death of Paulino Guajajara, from the Araribóia Indigenous Land, in Maranhão in 2019, was remembered by many. That case provided ‘a face and a story’ about conflicts in Indigenous lands. “The photograph of Paulino Guajajara looking at the camera, his face decorated with body paint, do you remember that? That image is so powerful!”

How to portray violence against these peoples was an issue that came up often in the interviews with journalists. “I feel that showing violence, blood, bruises, or lifeless bodies may have the unintended effect of pushing people further away. How to show violence intelligently in order to communicate what happened?”

Some of the interested but not non-engaged participants questioned what the public has been able to learn about land conflicts in Brazil from the images that have been shared on the subject in Brazil.

While recognising the tragic times Brazil is going through and the importance of denouncing violence and promoting acts of resistance, several people defended the need to expand our repertoire of images about life, the daily life, and the livelihoods of traditional peoples, in order to bring us closer together, and diversify the currently predominant visual narratives. “I think it is important to value their aesthetics, beauty, and grandeur. We always see them from a very sad perspective.” “Images have an immense power, and we still have few Indigenous images that empower and uplift.”

The books written by Davi Kopenawa and Ailton Krenak (“The Fall of Heaven” and “Ideas to Postpone the End of the World”) were cited as works that “create unique images about forests, and the cosmologies of Indigenous peoples”.

The records of Ailton Krenak’s speech during the 1988 Constituent Assembly, and of Tuíra Kayapó brandishing a machete before the president of Eletronorte were described as “historic”, “of enormous mastery and originality”, “genuinely iconic”, and “timeless”.

Sebastião Salgado was remembered for his monumental photographs and for the worldwide reach of his work, especially by interested and non-engaged participants. Among agribusiness representatives, in particular, Salgado was, many times, the only photographer and photos from Indigenous people mentioned; and apparently the only one known to them. “Actually, he is both voice and image. His images are powerful, but so is his voice” highlighted one of the scientists interviewed.

For non-engaged audiences, the image of Indigenous peoples was more closely associated with vulnerability than strength. “I would say that traditional peoples, unfortunately, are still a non-image for a large segment of Brazilian society”, said one interviewee.